Article

The Only Good Architect is a Dead Architect

Gideon Boie

2016, Oase Journal

Excessive attention to the notions of use and appropriation is symptomatic of a general malaise within Flemish architectural culture. Narratives of a rich public reception function as a phantasm that masks a lack of support and an uncertainty about the social relevance of the architectural discipline. What does the architect actually expect from the user? Can the user only appear on the scene after the great work of the architect is completed? Is the only good user a stupid user? And how can the user also become a vital component of the architectural production process?

User as fetish

It is noteworthy that notions of use and appropriation become the central points in a context where the architectural object disappears as a mere abstraction in special financial structures. This simultaneity was strikingly evident in the campaign by the Vlaams Bouwmeester (Flemish government architect) around architectural quality within the school-building program ‘Schools for Tomorrow’, a comprehensive public-private partnership between Agion (a Flemish government agency) and AG Real Estate (the real estate arm of BNP Fortis Paris Bas).1

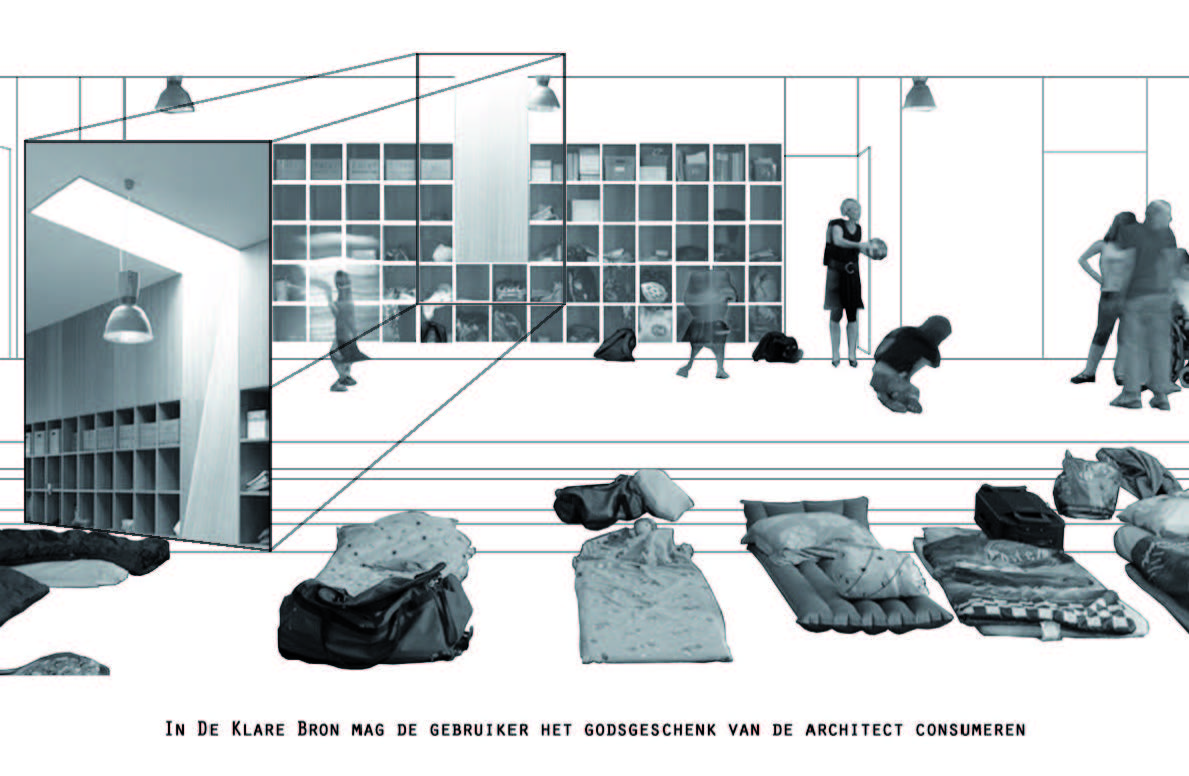

Use and appropriation function in this case as a fetish for that which was lost in complex and opaque mathematical models: an architecture supported by concrete needs and desires. How else can we explain that the primary school De Klare Bron in Heverlee was considered an example of best practice by the Vlaams Bouwmeester?

The design of the method school De Klare Bron was an early forerunner of the massive school-building program and was developed by MaccreanorLavington Architects following an Open Call for proposals. The design innovates on some fundamental aspects of the formal apparatus of educating children. The crowning piece is called the ‘living hallway’ (leefgang), a widened corridor that allows a purely functional space to also be used for activities. Coupled with the gymnasium’s collapsible wall, the ‘living hallway’ suddenly creates a sea of open space at the heart of the school.

The school’s unique user qualities, however, do not mean that the user—in this case, school management and teaching staff—was actually involved in the creation of the design. Defining the project brief, the appointment of the architect, and the development of the design was approached as a technical matter within the public-private partnership of the overarching school authority (GO!) and the financier / developer (BNP Paris Bas). In such public-private partnerships, the user remains an abstract reference and never becomes a contributing subject within the shared design process.

No wonder the school team responded indifferently when accepting this gift from God. It’s also ironic, then, that in the words of the architects themselves, the design did justice to the method school’s philosophy of encouraging student participation and emancipation. The design process itself was not subject to those same values. The architect remained lord and master in a design that reflects his good intentions. Use and appropriation only gained meaning in the consumption of the architectural object.2

Postproduction in architecture

The City of Antwerp’s acclaimed property readjustment policy brings us a step further in our analysis of the benefits of use and appropriation for architectural production. The objective to introduce architectural quality in small doses with ‘urban acupuncture’ inside the decrepit 19th century city belt, appears to have been realised only after the first user was banned from the design process. The property policy was created as a market operation with the autonomous municipal company Vastgoed en Pandenbeleid (AgVespa) at the steering wheel.3

The architectural quality of the single-family housing arises from a private agreement between AgVespa and a selected pool of architects. In the design process, young (and less young) architects were given almost total freedom to experiment within an imposed building envelope. A strict set of financial, formal and structural requirements ensured that the final product would still be a marketable design product.

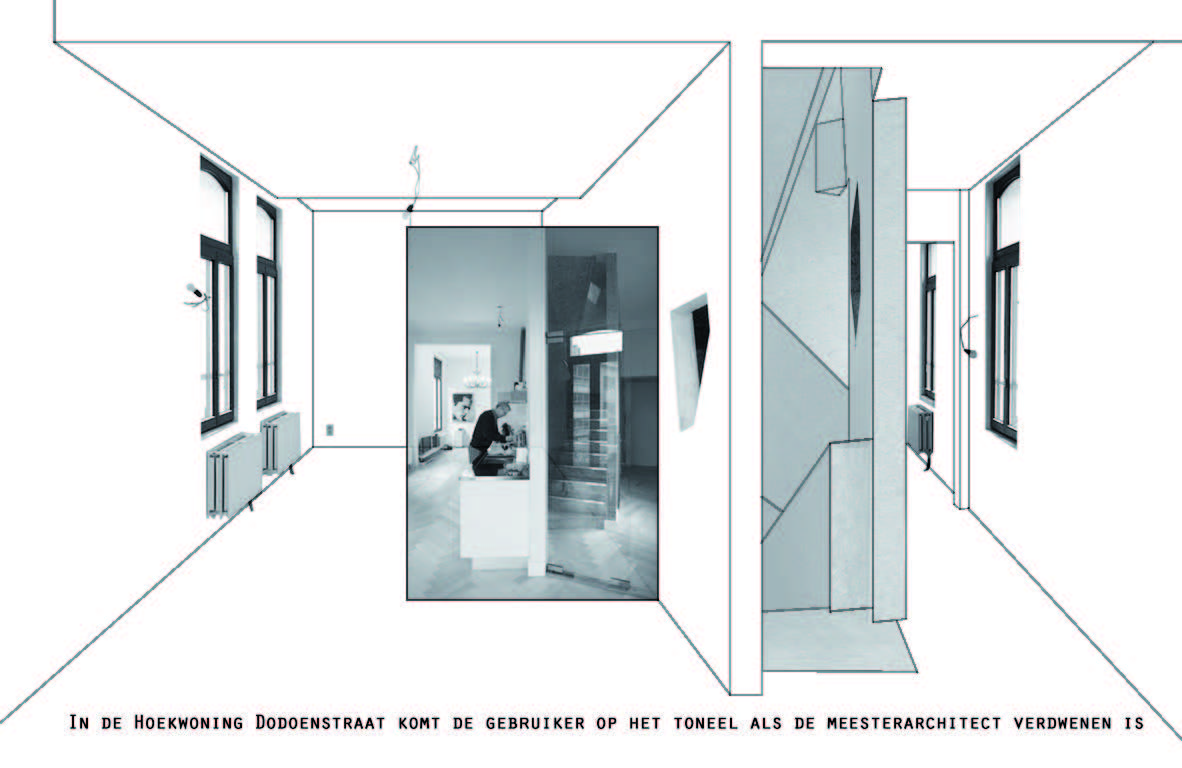

Designed by URA, the corner building on Dodoensstraat exemplifies the contradictions in Antwerp’s property policy.4 The architects’ main intervention was the angular spiral staircase created by an offset along the property boundary. It was an alternative to a traditional staircase that would have taken up a disproportionate amount of useful floor space in the narrow corner building. The placement of the spiral staircase in the centre of the space not only limits the footprint, but also enables a much more rational distribution of spaces.

Interestingly, the representation of the architectural projects that fall within the property policy invariably provide an intimate glimpse into cozy and contemporary interiors. The image contradicts the fact that the market operation is strictly limited to the delivery of the core. Thus we are allowed to see the decorated version of the corner building on Dodoensstraat, including the postproduction touches added by the end user.5 Here, too, the owner appears indifferent to the unique minimalist architecture. He has closed the light openings in the spiral stairs, extended partitions and sealed off spaces with French doors. Consideration for use and appropriation appear to be a marketing tool rather than a concern with the actual residential desires of the end user.

In the end, the images of use and appropriation in the corner building on Dodoensstraat also reveal the ideological nature of the property policy. The idea was to attract young middle class families by creating a new, architecturally tasteful identity for the 19th century belt. Ultimately, the end user in the corner building was not this intended user group, but instead an entrepreneurial man who promptly converted the single-family house into a bed and breakfast—although that makes no difference to the commercial logic of this transaction.

Appropriation by whom?

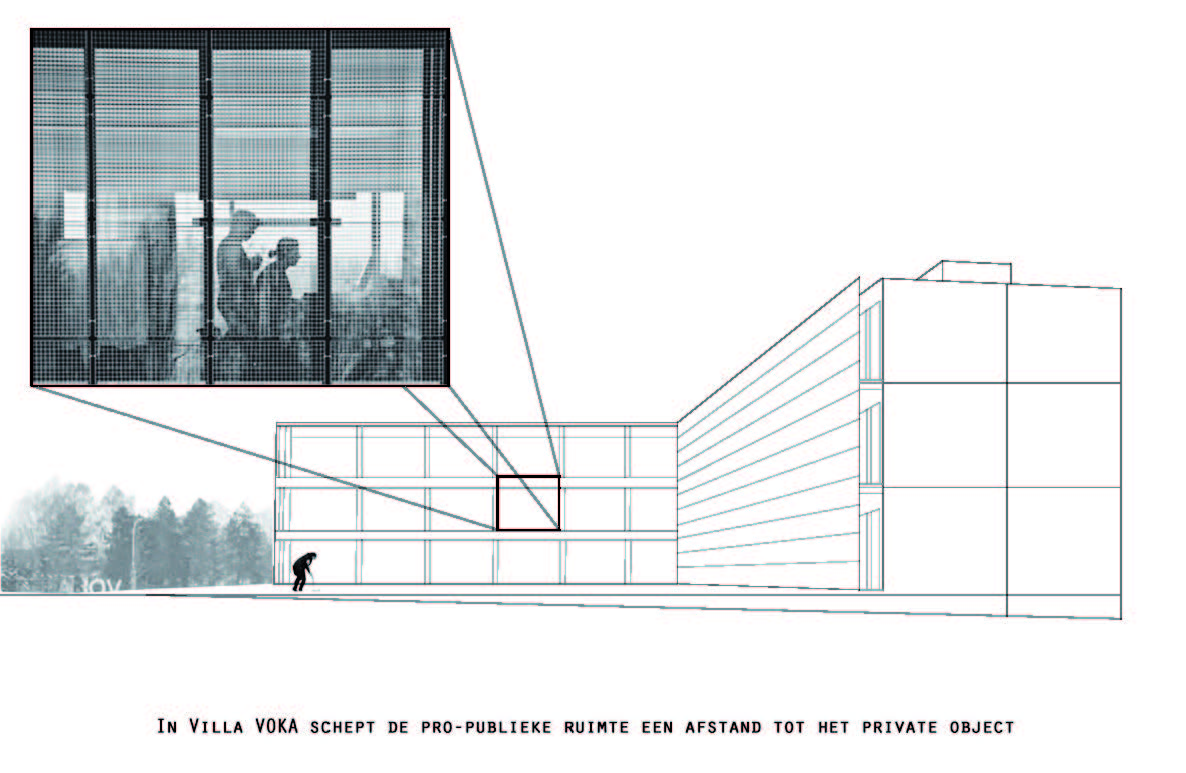

The continuing alienation or abstraction of architectural production is not solely due to the increasing importance of other heteronomous forces in the design. Conceptions of use and appropriation are equally rooted in the very autonomy of architectural practices. For example, in the work of Office KGDVS we see so-called ‘pro-public zones’ appear around a chamber of commerce, a villa, a school and more.6 A formalistic definition of architecture anticipates the representative (not to say fictitious) category of ‘the public’.7

It is in this atmosphere of absolute architecture that Flanders turns out so-called traversable building blocks, generous office buildings and alive street scenes. As beautiful as the results may be, it remains totally unclear who or what occupies the public space and for what purpose. An empty signifier is translated into space one-on-one. Use and appropriation operate here as a bargaining chip for an archaic division of labor between the architect (and master of design), and the user who consumes the design according to daily routines. The user is alien to fundamental design decisions regarding shape, proportion, material and texture and thus never gains the power to appropriate the production of the architecture itself.

Against the backdrop of this division of labor between Master Architect and naïve end user, it is more correct to speak of an appropriation of architecture by the architect. It is within the architect’s control whether or not the design brief becomes alienated from the client and transforms into a design that has meaning only within a specific oeuvre or design school—and as such, is recognised only by initiates. The user stands there and looks at it. In light of the architect’s appropriation of the architecture, the appropriation of architecture by the user is child’s play.

The question is: how can we undermine the perverse logic of use and appropriation? Some images by photographer Stijn Bollaert put us on the right track. The explicit demand to bring the end user into the picture in the annual Architectural Review Flanders (Architectuurboek Vlaanderen) was answered by most photographers with cheerful household scenes of children playing and struggling parents. In some photos, Stijn Bollaert answered the question of ‘use’ by repeatedly bringing himself into the picture.8

The photographer’s cameo appearance successfully undermines the ideology of use and appropriation. The inclusion of the photographer in the picture makes us aware of the imposed frame within which architectural production is captured in Flanders. In various representations, we see the same phantom wandering against the background of absolute architecture. In one image, the suggested user is a figure that awkwardly and uncomfortably descends the stairs. In another picture, it’s a dreamlike figure leaning over a wall, appearing to admire its own architectural creation.

The series of images by Stijn Bollaert shows exactly how the ideology of use and appropriation functions: it reduces the user to an interchangeable attribute within abstract architectural representations of ‘the public’. A general wisdom among architects is that architecture can best be photographed during that mythical moment just prior to delivery—before the creation is stained by users who install all kinds of tacky furniture or introduce dissonant uses.

User as Subject

We have to take another step to come to a subversion of the ideology of use and appropriation in the design. Our argument is not about exposing the user as an illusion, since the idea of an absolute architecture feeds on the same fantasy. The point is that the user-as-fetish can also be interpreted positively. Bollaert’s photographs show like no other the failed longing to make the user part of architectural production in Flemish architecture. All of the above challenges us to remain faithful to the desire and to give the user an effective voice in the design process. Only in this way can the acclaimed Flemish architectural culture become a living part of society.

One Flemish example where the user is not just an afterthought, is ParckFarm, a project that has already been discussed elsewhere in this issue. The interweaving of exhibited work with local initiatives has been key to ParckFarm’s success. Use and appropriation was not an afterthought, but part of the production process. The result is an eclectic collection including a farm house, landscape table, compost toilet, bread oven, sheep meadow, chicken coop, beehives, lighting, etc. The roles of the curators (Taktyk and Alive Architecture) and architects (including 1010A + U, Collective Disaster and students from Sint Lucas) were as fundamental as the contributions from Ruth, Tessa, Abdel, Moustafa, Nadine, Christina, Sennouni, Susan, Abdelali, Jorgue, Mario and others. It is completely unclear for the uninitiated—and irrelevant—where the work of one stops and the other takes over.

ParckFarm is the big exception in contemporary Flemish architecture and even said to be no architecture. This is not entirely incomprehensible, because the unusual architectural practice behind ParckFarm undermines dysfunctional concepts of ‘architect’ and ‘user’. In a project like ParckFarm, architectural production is no longer the idiosyncratic product of some master architect, but the result of a shared desire that is constructed at the intersection of the architect-curator and the user-architect.9 It is only possible for the architect to create spaces for actual needs and desires in the form of a curator or mediator. And for the user, it is only in the form of co-producer that they are able to become a genuine and real support base for architecture.

Source:

Article published in Oase Journal #96, Social Poetics The Architecture of Use and Appropriation, 2016, 44-50.

Captions for images

- De Klare Bron, Heverlee, Maccreanor Lavington Architects

The user is allowed to consume the architect’s gift from God.

- Corner building on Dodoensstraat, Antwerp, URA

The user enters the scene when the master architect has disappeared.

- Villa VOKA, Kortrijk, Office KGDVS

The user respects the laws of absolute architecture.

- Photo’s by STIJN BOLLAERT

Notes:

- http://www.scholenbouwen.be/schoolvoorbeelden/bs-de-klare-bron-heverlee. See also: Maarten Van Den Driessche (ed.), De school als ontwerpopgave: Schoolarchitectuur in Vlaanderen 1995-2005 (Gent: A&S Books, 2006).

- Alain Findeli and Rabah Bousbaci, ‘L’éclipse de l’object dans les théories du projet en design’, The Design Journal 8 (1) (2005), 35-49.

- See also: Gideon Boie, ‘Architectural Asymmetries’, in: Ana Jeinic and Anselm Wagner (eds.), Is There (Anti-)neoliberal Architecture? (Berlin: Jovis, 2013), 104-117.

- Katrien Vandermarliere et al. (eds.), The Specific and the Singular / Architecture in Flanders 2008-2009 (Antwerpen: VAI, 2010), 188-191.

- Nicolas Bourriaud, Postproduction (New York: Lukas & Sternberg, 2002).

- Aglaée Degros, ‘Vlaams Eldorado’, in: Christoph Grafe et al. (eds.) Architectural Review Flanders nr. 10 (Antwerpen: VAI, 2012), 115-138.

- Pier Vittorio Aureli, The Possibility of an Absolute Architecture (Boston: MIT Press, 2011).

- See, among others: C-mine (design 51N4E): http://www.stijnbollaert.com/

- Doina Petrescu, ‘Losing Control, Keeping Desire’, in: Peter B. Jones, Doina Petrescu and Jeremy Till (eds.), Architecture and Participation (London: Routledge, 2005), 43-64.

Tags: English, Vlaams Bouwmeester

Categories: Architecture

Type: Article