Article

Living in a mental institution

Gideon Boie

2013, Psyche

Image: UR architects

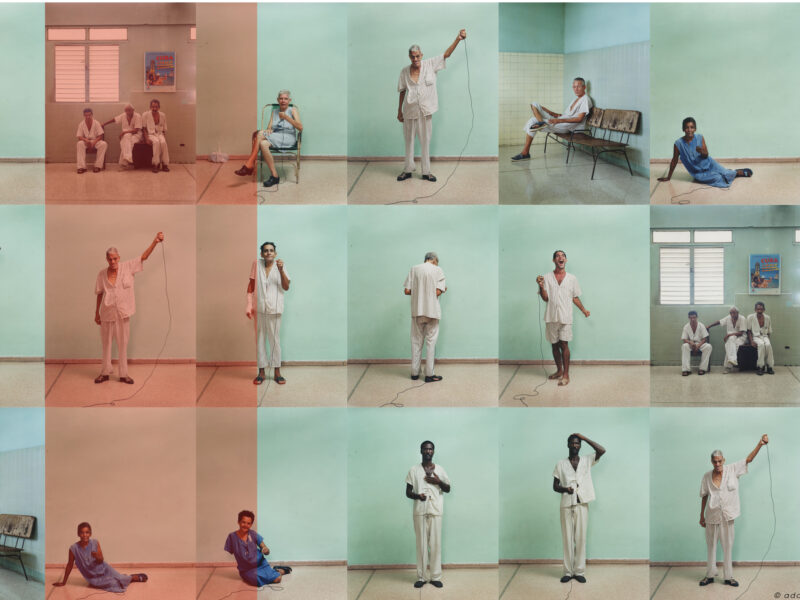

There are limits to the socialisation of mental health care. Traditional mental institutions retain their right to existence in the light of the need for low-stimulus environments in care. At the same time they represent a substantial spatial and symbolic wealth which from a business point of view cannot simply be eliminated.

In this context, UR Architects launched a piece of design-based research into the future of the Sint-Amandus Psychiatric Centre in Beernem – part of the Brothers of Charity npo. They did so at the request of the Flemish Architecture Institute in the framework of the ‘Young Makers, Thinkers, Dreamers’ programme.

Their design-based research includes a limited analysis of the site. It was apparent from this that there was no coherent, well-considered vision for the spatial development of the institution site. What is currently called a spatial master-plan is more of a technical application of bed capacity to built volume. There is also some fairly obscure ongoing horse-trading with heritage departments regarding the preservation of one or other building.

The disregard for quality objectives in the areas of architecture, space and heritage is in sharp contrast to the psychiatric centre’s prominent presence in Beernem. With 470 beds in the hospital and 147 beds in the care home, Sint-Amandus accommodates a great many of the inhabitants of Beernem. This strong link means that in this region the names Sint-Amandus and Beernem are interchangeable.

The second section of the design-based research is a proposal to give what is called the ‘Oude Bouw’ (Old Building) a standardised housing programme. This 19th-century building of no less than 180 metres in length has several unique characteristics – in terms of scale, image, location and surroundings – that fit well with the local demand for lofts, three-room flats, family homes with gardens, service flats and twin housing. This gives rise to an opportunity to create a housing environment where patients can be admitted onto a non-clinical setting.

A new psychogeriatric department is added to the back of the Oude Bouw. In this way the traditional view of the Oude Bouw from the street is preserved. The suggestion of a block of buildings with a mixed housing programme at varying elevations is even more important. In this way the roof of the new building provides an extensive green zone for the homes. Its central location guarantees easy access to the sports hall, function room, chapel and other facilities.

The fact that this is design-based research means that it is possible to depart from the often forced serviceability of a design brief. By means of a visionary design, UR Architects want to generate practical design knowledge concerning concrete questions which do not usually even arise in a building assignment.

Firstly, the proposal is intended to make a start on a spatial master-plan that redesigns the institution site on the basis of a positive plan. The condensation in and around the Oude Bouw initiates not only a new use of space, but also the use of the existing facilities such as the theatre building, pharmacy, sports hall, chapel and so on. In this regard, the landscape and the visual relationship between the buildings function as a connecting link.

Secondly, the design-based research puts a stop to the never-ending cycle of demolition and new building. The introduction of an alternative programme into the Oude Bouw offers a meaningful scenario for the preservation of another specimen of care heritage that is currently on the list for demolition – like the modernist chapel. The reason for demolition is usually the rule that the relevant government department, the Flemish Fund for Person-Based Infrastructure (VIPA), only subsidises new building, plus the notion that dated hospital architecture has a stigmatising effect.

Lastly, the new programme in the Oude Bouw achieves an inverse socialisation of mental health care. The socialisation of care represents the embedment of residential care in the normal urban fabric – by means of psychiatric care homes, sheltered accommodation and suchlike. The proposal follows the Dutch model and introduces a normal housing programme into the heart of the remaining critical care centre. This gives Sint-Amandus the opportunity to develop into a normalised housing environment.

In this way we see how the housing market is deployed as an instrument to achieve objectives in the areas of spatial quality, the preservation of the heritage and a care plan. Since no prior examples exist, it is hard to predict whether the effect of the market will live up to the great expectations. However, the crucial question is whether all the parties involved are ready for the marketisation of Sint-Amandus.

A measure of the degree of support was the presentation of the design-based research at the Flemish Architecture Institute, attended by many of the parties involved. It was notable that the audience above all expected more from the inverse socialisation at Sint-Amandus.

On the one hand there was some confusion about the somewhat generic demand of the market. The design-based research does not clarify patients’ need for housing programmes on the institution site that are not in accordance with the sensitive care programme. Nor does it become clear to what extent the patient may have changing housing wishes that cannot be fulfilled by what is currently on offer. On top of that, combining psychiatric care with housing programmes for the elderly or disabled seems to turn the clock back. This confusion gave rise to the question of the extent to which social and cultural functions might be a more effective means of inverse socialisation.

On the other hand the focus on the monumental Oude Bouw was too easy. The mistaken suggestion of an exclusive housing programme was encouraged by a far-fetched argument about gentrification, which is the social, cultural and economic upgrading of a part of a town. Among the comments on this, a pertinent one was that the new group of housing consumers in the Oude Bouw does nothing to change the isolation of the institution’s site in the normal fabric of the town of Beernem – which still remains on the other side of the E40 motorway. This discussion was put in sharp focus in the question of whether laying out a real village structure at Sint-Amandus would not be more suited to the objective of inverse socialisation.

To set the future of Sint-Amandus in motion, the design-based research has to show that inverse socialisation is not the easy option.

Published in Psyche 24 (4), December 2012, quarterly magazine of VVGG

The design-based research ‘The Future of the Asylum‘ was presented on September 25, 2012 in the Flemish Architecture Institute (VAi). The debate hosted Nikolaas Vande Keere and Regis Verplaetse (UR Architects), René Stockman (General Superior of the Brothers of Charity), Prof. Em. Luc Verpoest (KULeuven), Wivina De Meester (former state secretary and founder of Huize Monnikenheide), Christoph Grafe en Katrien Vandermarliere (VAi).

Tags: Care, English, Psychiatry

Categories: Architecture

Type: Article