Article

Models of Inclusion

Gideon Boie

June 2022, E-flux

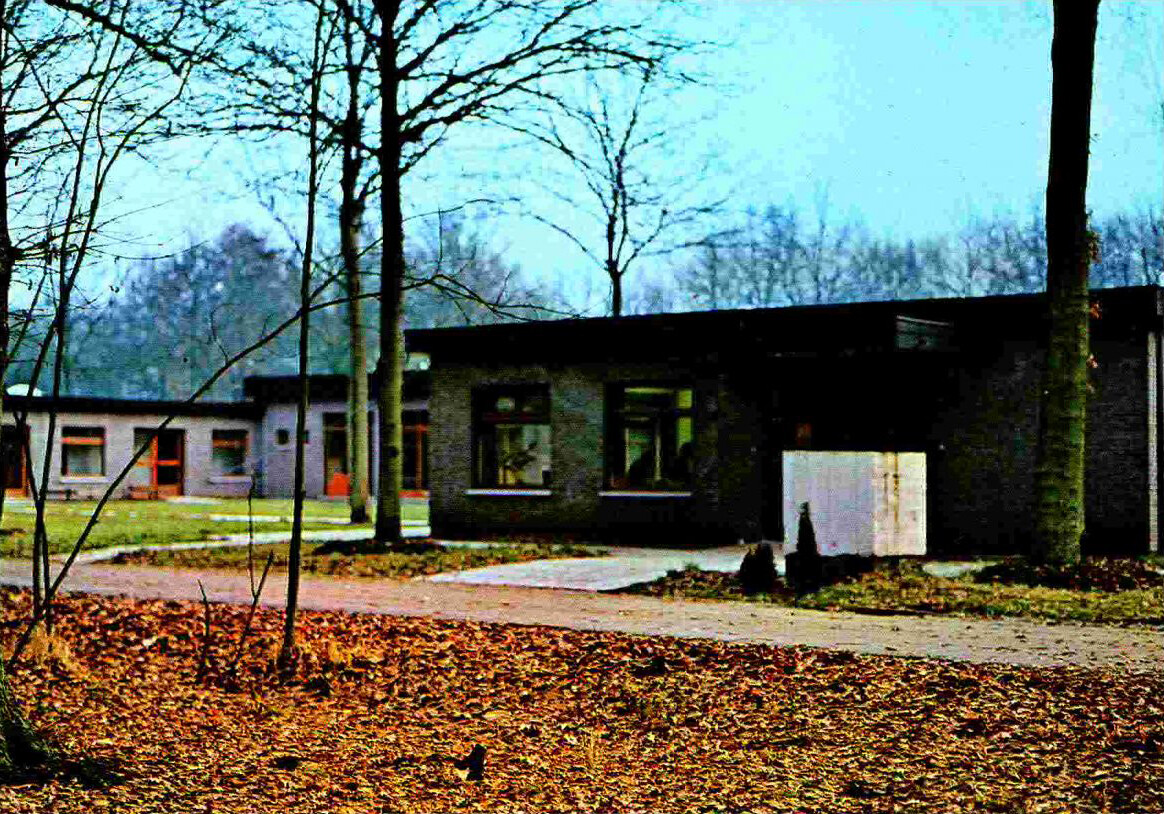

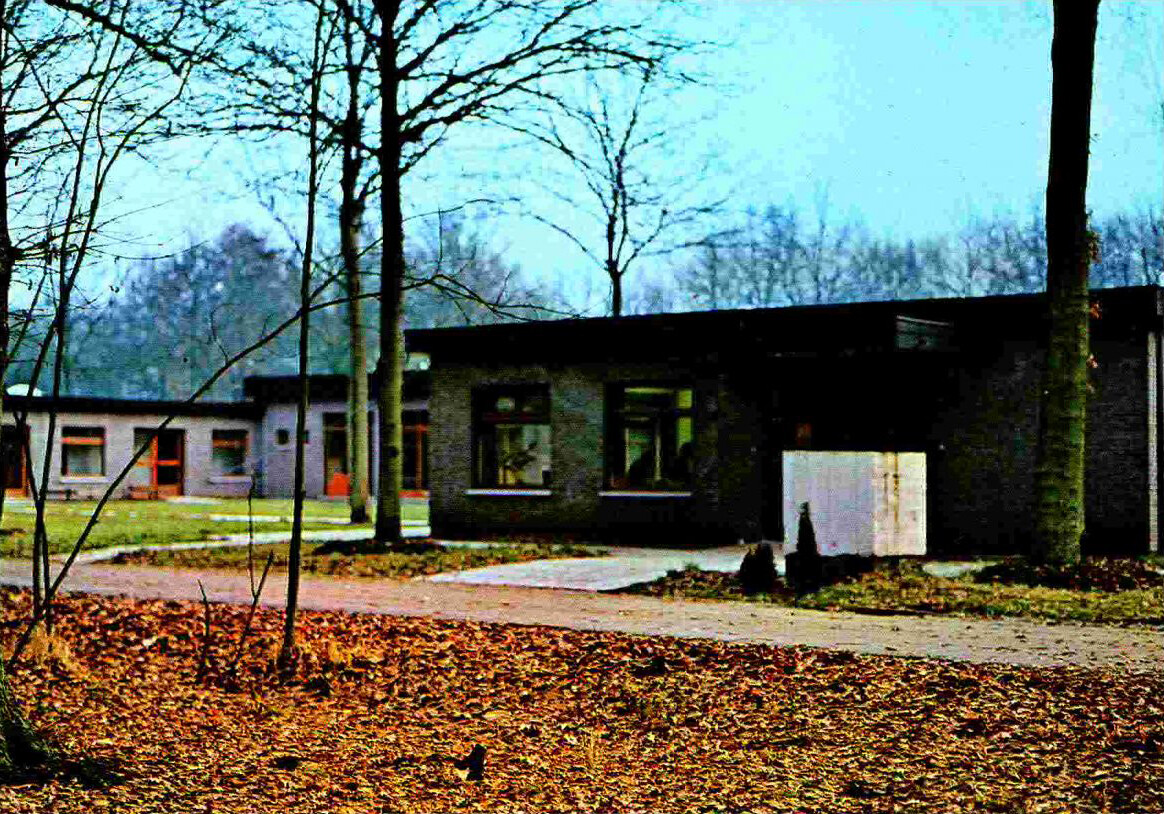

Image: unknown, Monnikenbos (1980)

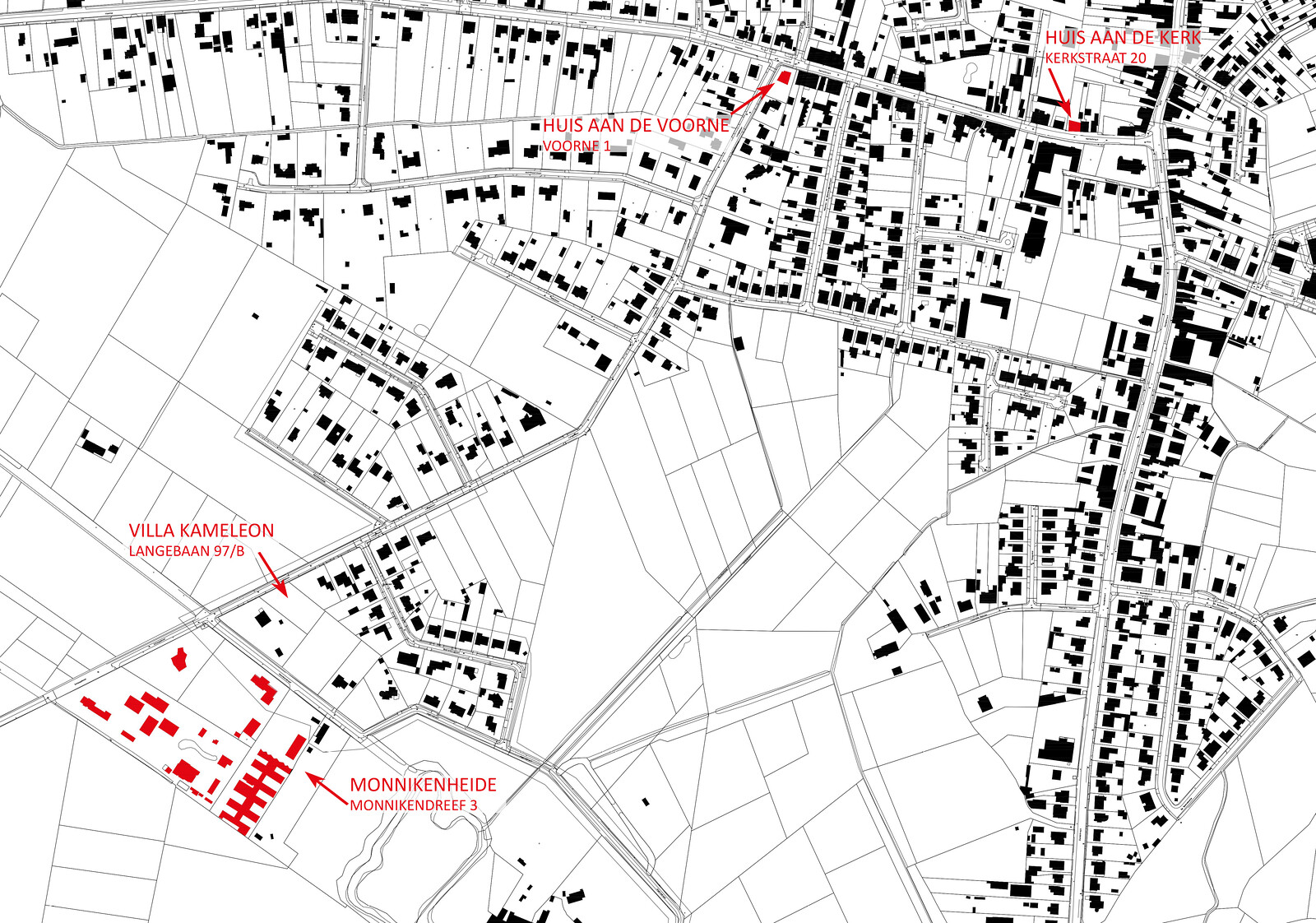

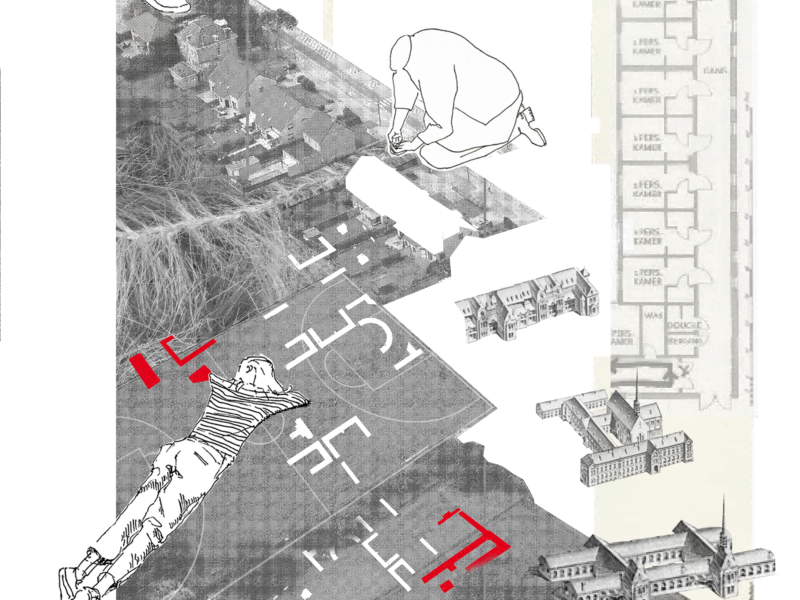

Liberated from the exaggerated dreams of a healing environment, architectures of care can repair the old logic of separation for persons with mental and physical disabilities, which often ended up in segregation. The re-introduction of the disabled person in society is one part of the challenge of inclusion. Aligning spatial settings and housing models to their special and changing needs is another, as is the reverse: questioning how architecture can support citizens to take up ordinary care tasks for their disabled neighbors. The experimental architecture at Monnikenheide, a residential care complex for persons with disabilities in Zoersel, Belgium, has addressed inclusion as a dynamic design challenge since it was founded in 1972.

The history of Monnikenheide begins with its founders, Wivina and Paul Demeester.1 As member of the Flemish Christian-Democrat party, Wivina Demeester was state secretary in several federal and regional governments from 1985–1999, during which time she held roles in healthcare, welfare, and public administration. She has also been a decisive figure in the landscape of architecture in Flanders, playing a foundational role in the development of both the position of the Flemish Government Architect and the Flemish Architecture Institute.2 Her interests in politics, care, and architecture culminated in the search for an appropriate living solution for the couple’s son, Steven, who has Down syndrome.

In the 1970s, disabled persons were often still living either in or at the margins of psychiatric institutions. According to Wivina Demeester, they reached a breaking point when searching for an accommodation for their son, specifically on a visit to the well-known Stropstraat in Ghent, the main campus of the Brothers of Charity, which provides care services for all sort of sick, mentally ill, and disabled persons.3 After the visit, the Demeesters began their endeavor to provide alternative housing that radically includes disabled people in society and recognizes their specific territorial needs and desires.4 At Monnikenheide, the traditional logic of asylums with large “bed houses,” was replaced with an open setting of small-scale facilities that operate as substitute families.5

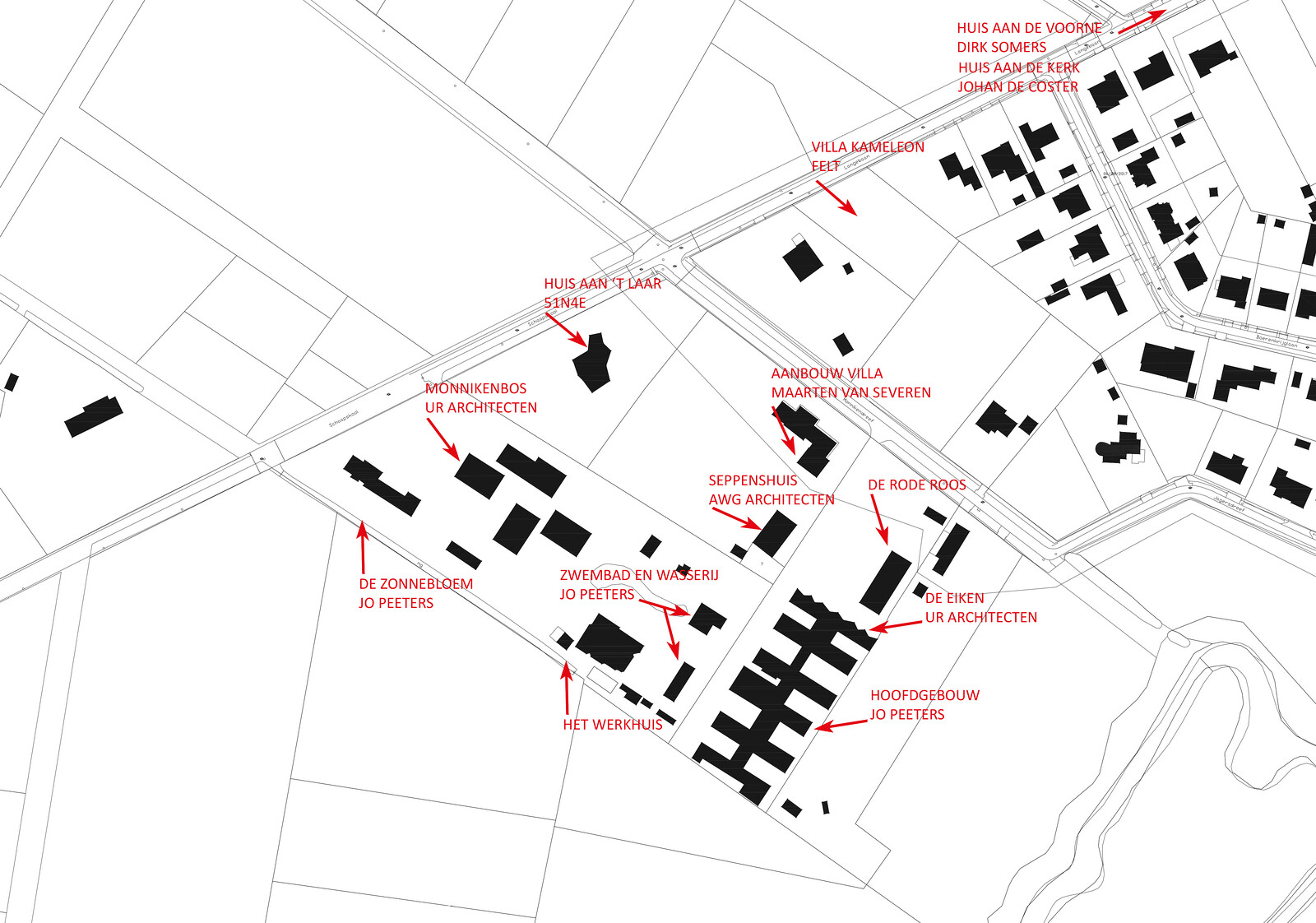

Monnikenheide is comprised of a series of residential facilities built as part of a suburban allotment, a typical settlement pattern, in the Kempen region. Its facilities are spread out on a wooded terrain in the back of the Demeester family villa, which is located on the edge of natural reserve. The built projects differ from one another, but what is more important than their aesthetic differences is the design intelligence that was realized in experimenting with architectural typologies and spatial settings.6 A walk through Monnikenheide today presents an evolution of care, following progressive insights on how architecture can support the inclusion of disabled people.

The first short stay building complex, designed by Bruno Boulanger (1973).

Family replacing units

The architecture of Monnikenheide is defined by an evolving typology of the family replacement unit, which allow for small groups of residents to function quasi-independently. The first short-stay home, which was designed by Bruno Boulanger in 1970 and today functions as the central service building, originally consisted of three identical pavilions. Built using the Danilith prefab system, a single corridor connected the common services pavilion in the middle with the boys and girls pavilions on both sides. With large capacity in its collective sleeping rooms, the repetition of pavilions sharply contrasts the classical dormitory typology used in hospitals. This focus on small-scale units is recognizable in all other buildings on the site.

Renovation and expansion of the first short stay building complex by Jo Peeters (2003).

In its 2003 renovation by Jo Peeters, the building’s capacity got reduced to one resident group per pavilion, with living rooms placed on one side of the corridor and individual sleeping rooms on the other. The central corridor was also extended, and a fourth pavilion added in the row. The spine knitting all pavilions together was transformed with huge glass windows to make sure it does not feel like a hospital corridor. A laundry and therapy pool were built opposite the building’s new entrance, which as separate facilities are meant to stimulate the use of the exterior and enhance the dynamic of going in and out. The recent building of De Eiken (2017), designed by UR architects, added an additional fifth pavilion to the spine, with a façade that suggests it is the end of the line.

Spaces of Inclusion

The architecture of Monnikenheide also uses its spatial surroundings for the inclusion of persons with mental and physical handicap. The idea was to free disabled persons from the logic of asylums by situating them in the normal urban and social tissue, more precisely typical Flemish suburbia. The center is built as an open domain in the woods. Pavilions are scattered around the Demeester’s estate, and the residents are encouraged to not just use the small-scale units adjusted to their specific care needs, but also roam around in the woods, the neighborhood, and even in the village center, all without, if possible, being accompanied by staff.

Intertwined lines of operation

Sheltered housing is not only about its spatial setting; it shows also variations in the typology of a care home, and specifically in the arrangement of studio-like rooms in relation to common rooms. In the House at the Voorne, the communal space remains rather limited and bare, as the living room is simultaneously the dining room, kitchen, and atrium, with the individual rooms designed as studios equipped with a kitchenette. The internal logic of the House at the Church, however, is designed more similarly to a classical house with focus on the living room and kitchen, which function as cozy and familiar communal spaces, and an open staircase that leads to the individual rooms upstairs.

Notes

1

This article draws upon ongoing research conducted together with Vjera Sleutel (BAVO). The history of Monnikenheide is documented in: Wivina Demeester-De Meyer, Kris De Koninck, and Johan Vermeeren, eds., Monnikenheide “40” (Zoersel: vzw Monnikenheide, 2014).

2

The history of the Vlaams Bouwmeester (Flemish Government Architect) is documented in: Marc Santens and Jan De Zutter, Het Vlaams Bouwmeesterschap 1999-2005 (Antwerp: Uitgeverij Houtekiet, 2008).

3

Lecture at colloquium “Adieu to the Bed House,” organized by the Museum Dr. Guislain, Ghent, September 24, 2019. See the report at the website of Flemish Architecture Institute, ➝. Short version of the address published in the A+ issue on care architecture, A+ 283 (2020).

4

In an interview Wivina Demeester referred to the territorial approach by Cornelis B. Bakker and Marianne K. Bakker-Rabdau as the motivation for the family replacement units, May 5, 2021. See: C. B. Bakker and M. K. Bakker-Rabdau, No Trespassing! Explorations in Human Territoriality (San Francisco: Chandler & Sharp Publishers, 1973).

5

The “bed house” is a neologism, first used by a patient at the Karus psychiatric center, who added the prefix “bed” (i.e. the calculation unit for government funding of hospitals in Belgium) to “ziekenhuizen” (“hospitals”). It is used as a name for the large-scale hospital facilities mainly consisting of bed rooms, stripped bare from other necessities of life. See: Gideon Boie, “Design Your Symptom.” In: BAVO and architecten De Vylder Vinck Taillieu, Unless Ever People (Antwerp: Flemish Architecture Institute, 2018), 186–223.

6

Michael Speaks argued how design intelligence is constructed through daily chatter rather than fixed typologies and heroic forms. See: Michael Speaks, “Design Intelligence.” In: A. K. Sykes, ed., Constructing a new agenda (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2010), 204–215.

7

Michel Foucault argued how the program of resocialization was, after all, a strange thing considering the fact that we first separate these people. Although justified as critique, the argument does not take into account that separation might be necessary in some delicate care programs. See: Michel Foucault, Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason, (New York: Vintage Books, 1961), xx. Slavoj Zizek argued how the Hegelian synthesis is not so much a peaceful reconciliation of opposites, but the “negation of (the first) negation.” See: Slavoj Zizek, The Ticklish Subject (London: Verso, 1999), 72.

—

Sick Architecture is a collaboration between Beatriz Colomina, e-flux Architecture, CIVA Brussels, and the Princeton University Ph.D. Program in the History and Theory of Architecture, with the support of the Rapid Response David A. Gardner ’69 Magic Grant from the Humanities Council and the Program in Media and Modernity at Princeton University.

—

Text ‘Models of Inclusion’ published by E-flux, June 2022 in the Sick Architecture article series

Categories: Architecture

Type: Article