Article

Another space for care

Gideon Boie

20/12/2021, Psyche

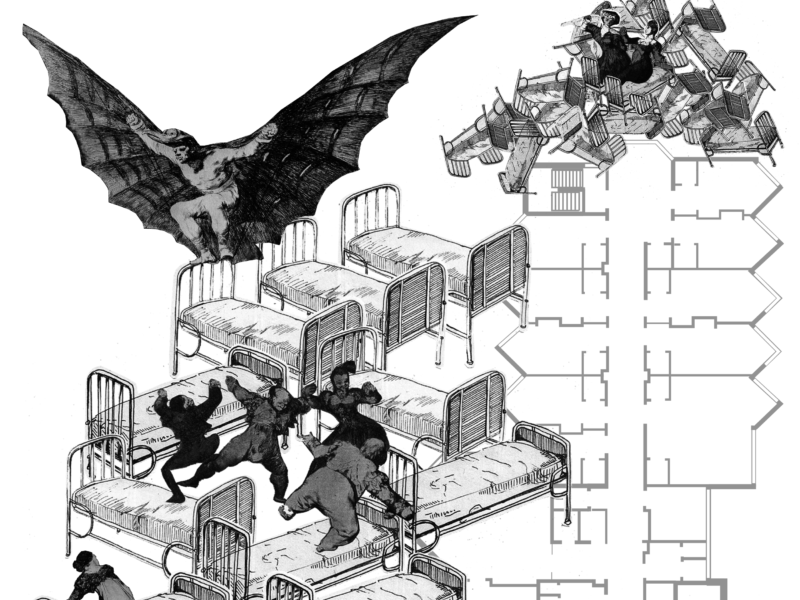

Image: Oona Valonen

The Villa Voortman meeting house features as a paradigm model for caring neighborhoods in the Big Fix-Up, a program that wants to outline the necessary transition of the living environment in Flanders. It is remarkable to say the least. A modest initiative operating in the fringe of large care institutions dealing with most vulnerable people, even located in the interstices of the city, gets linked to the major challenge of urban change. In the following article I leave aside speculation and first try to sketch the peculiar spatial setting of Villa Voortman.

The story of Villa Voortman started in 2010 within the villa of the same name on the Blaisantvest. In the empty villa a meeting house was set up that opens its doors daily from 9 am to 5 pm for people with dual diagnosis. The combination of substance abuse and psychological problems makes it difficult for these people to find a place in the regular psychiatric services or shelters and therefore they risk ending up on the street. Villa Voortman does not offer treatment or cure, but in the spirit of the recovery method it aims at restoring a meaningful life.

At Villa Voortman, we do not talk about patients or clients anymore, but about visitors. Drinking coffee and making music are the main activities in the house. It stand for the central functions of meeting and creativity. The creative sessions are even brought as socio-artistic work, often guided by professional artists, and ending up in festivals or publications. Also care is provided, though not residential and curative. The care includes a bed for daytime use, shower facilities, hot meal and administrative help. In everyday practice, the three functions are of course intertwined.

The original villa was the home of the directors of the former textile factories on the grounds where several hospitals were later built, including the general hospital Sint Lucas and psychiatric centre Gent-Sleidinge. The dilapidated building served as eccentric setting for socio-artistic activities and low-key meetings. The furniture comes from the thrift store. The easy accessibility from working-class neighborhoods like Rabot and Wondelgem was a plus, while the proximity of the psychiatric center and general hospital was ideal for support.

In an ironic twist of history Villa Voortman lost its housing in 2016 when the construction began of a large-scale development concentrating all sort of care programs. The project development consists of luxury service flats, assisted living, care hotel, regular housing, and other special services. It shows how the precarious target group of Villa Voortman threatened to slip between the cracks, simply not fitting the ponderous real estate plans. Finally the meeting house was offered an alternative in a complex of elderly housing in a cul-de-sac of the Vogelenzangpark (nrs. 10-17).

While waiting to move to the Vogelenzangpark, Villa Voortman was accommodated in a house within the Small Beguinage in the Lange Violettestraat. Once again, the dilapidation was a grateful starting point for the socioartistic work and the furniture was collected from the thrift store. However, the location was said to be less than ideal in terms of accessibility for visitors, who now had to cross the entire city. Also, the successive moves caused a lot of inconvenience and unrest to the visitors.

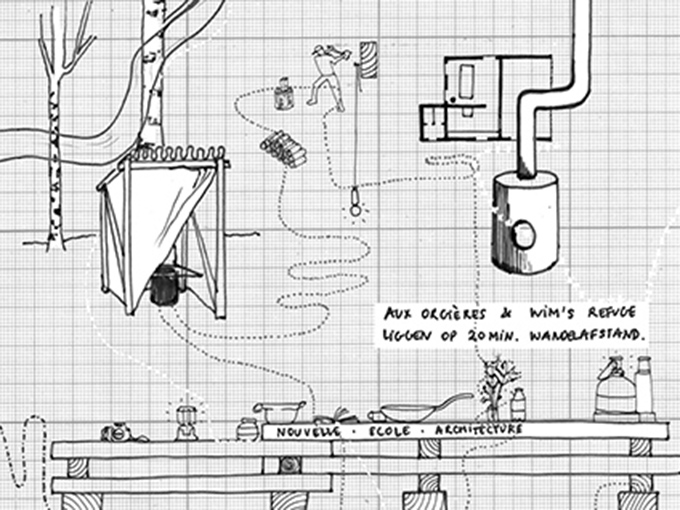

Since spring 2018, Villa Voortman moved to the complex at the Vogelenzangpark, basically eight identical modernist bungalows built in 1961. The main infrastructural intervention is the creation of a passageway between the eight houses, creating an enfilade of rooms that provide space for the different activities, such as the music room, painting studio, kitchen, dining table, lounge and office. The absence of a hallway enhances the clarity of the large interior space, while still respecting the former houses as so many corners. Hidden in a back room stands the bed.

The spatial setting of Villa Voortman is also characterized by the use of the park as an extension of the meeting house. The miniscule back gardens are kept unused, making it seem as if the meeting house even does have a backside and only orients to the front yard. In the park there are a number of picnic tables that are used extensively. The window sills are also used as seating. A notable novelty with the first years of operation is the new driveway to the general hospital that today cuts right through Vogelenzangpark.

Just as important as the physical provision of Villa Voortman is its operationalization, thanks to activities set up in consultation with the visitors. Villa Voortman presents another space that invites the visitors to use and appropriate it. It brings us to the paradox – stated on the website – that in the absence of a structural therapeutic program, some activities can nevertheless have a therapeutic effect. The paradox is perhaps the best clue to the question what we can learn from Villa Voortman for the big fix-up of the living environment in Flanders.

The Flemish Government Architect once spoke of the need for invisible care, it was about an idea of care that is a seamless part of the urban environment. It was also about a concern that distances itself from the industrial-sized bed houses where you can go for any illness and find an architectural logic that goes beyond the cheap label of healing environment, lubricant for huge real estate developments. In this light, Villa Voortman can be described as an architecture that does not have the slightest pretense of contributing to healing and may be for this reason the best example of a healing environment.

Draft translation of an article originally published in Psyche 33 (4), periodical of the Steunpunt Geestelijke Gezondheidszorg, November 2021-January 2022.

Image: Oona Valonen

Tags: Care, English, Psychiatry

Categories: Architecture

Type: Article