Article

Don’t say Lente to the new Lente

Gideon Boie

2018, Flanders Architecture Institute

Image: Filip Dujardin

A chance encounter with a patient in the Kanunnik Petrus Jozef Triest Plein redeems us from one last obsession: the belief that architecture finds its moment of glory in the delivery of the building project. In the case of the Jozef Plein, the most important result is perhaps not so much located in itself, but in its legacy.

It is nightfall on a late summer’s day (15 September 2017) when I arrive at the centre with two close friends. In the twilight a lady wanders through the monumental outdoor space. She asks me politely what I am looking for so late at night – as though I were an intruder in her realm. In the ensuing conversation, she appears to have been hospitalized for a few weeks now. It is her first stay in psychiatry in a long time. The lady conveys a great admiration for the monumental outdoor space. She admits to not knowing what the function of the building is, but pays a visit night after night. With this, the patient unwittingly lifts the realization of architecture beyond its delivery. It is not so much in the design, but rather in the everyday evening walk that we see the realization of the original desire for a ‘wishing wall’ – the fantasy that, in condensation with other desires, catalysed the management to halt the demolition of the Sint-Jozef building back in December 2014. The circle of architectural production is somehow closed as concept and reception coincide in the lonely activity of a daily evening stroll.

As we continue the walk, the woman expresses regret over the disrespect manifested by others for the building. She says: ‘The drawing in the cellar is very sad, so ugly and so black.’ It seems like a big surprise when I suggest: ‘Why don’t you draw something prettier? That’s exactly what these white walls are asking for.’ The lady confesses to being an amateur in chalk drawing and promises to bring along her chalk sticks on her next walk. And so it happened that only a few weeks later I found a large rainbow drawn next to the doorway in the cellar with the inscription ‘You are my sunshine’. Also, the black painting had been slightly recoloured. It reminds me of an evaluation meeting (29 June 2017) in which we discussed the seemingly slow process of use and appropriation in the undefined space. General director Herman Roose situated the challenge in what he called the ‘limited transfer of events’ within the psychiatric centre. The Jozef Plein may be conceptualized as a ‘space of possibilities’ within the psychiatric centre, but it is not always clear to patients what is allowed or not within this open space, let alone that uses are transmitted from one to another. The confrontation with the chalk drawing makes me realize that my light-hearted suggestion triggered a mental opening in the accepted boundaries of the possible that limit the use of the open space.

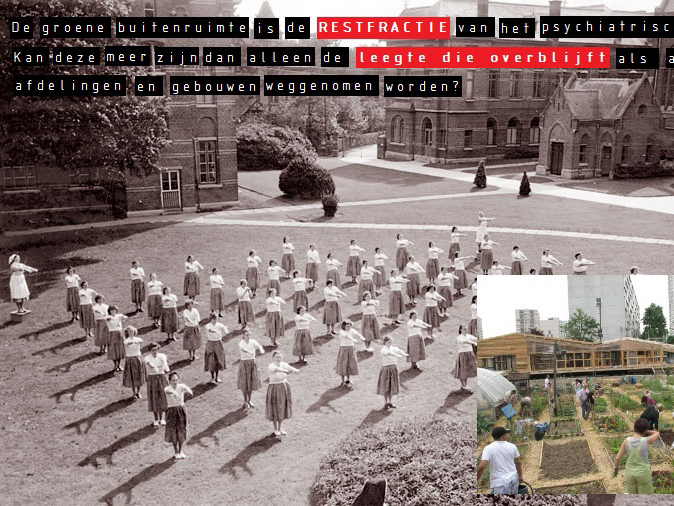

There is yet another element in the conversation with the patient that situates the result of architecture outside itself. The woman not only praised the Sint-Jozef Plein, but went on to say: ‘The “Dageraad” [“Dawn”] is also such a beautiful building.’ The reference to Dageraad – the department for psychosis care – caused some confusion in our talk. From the very beginning of the vision development, it was exactly that specific building that came to symbolize, for patients and staff alike, everything that was wrong with the new quasi-modern architecture in the psychiatric centre. The Dageraad department was located, together with its Siamese twin ‘Klimop’ (‘Ivy’), in the expansion area of the hospital across the ‘Heidestraat’ (‘Heather street’). Despite the suggestion of a holiday park-like architecture in a green, Arcadian landscape, the complex building for Dageraad and Klimop was described as oppressive, claustrophobic, disorienting and worse.

After double-checking I found out that the lady was actually referring to the renovated Lente building which the Dageraad department had moved into since 21 March 2017. The story of the Lente building is entangled with the Sint-Jozef renovation, as the contracts for demolition were signed and budgets reserved accordingly. Only a temporary lease of the Lente building to ‘De Heide’ (‘The Heather’), a centre for people with physical disabilities located in the village of Merelbeke, delayed execution. The Lente building finally got saved in the same contract renegotiation as the Sint-Jozef building. It was the vision of the psychosis work group, headed by psychiatrist Dr Celine Matton and psychologist Inge De Paep, that the building characteristics of the historical Lente building better meet the spatial needs of psychotic patients. The team pursued the ideas put forward in the psychosis work group, taking matters into their own hands. They engaged interior designer Philippe Allaeys for advice and furniture design, visited Jules Thielens’ reference project ‘The Brewery’ in Amsterdam, closely following the building plans drawn up by the technical team, etc. Today not only the lady but staff too praise the building’s clear spatial layout, its spacious living rooms, high ceilings, short corridors and easy access.

The reference to Dageraad made clear that the lady was speaking of the new reality in the Caritas Psychiatric Centre, not limiting her attention to the architectural object. The design by architecten de vylder vinck taillieu is rightly getting a lot of (media) attention, although it does not solve much as such. Undoubtedly the question about what to do in the sublime emptiness of the Jozef Plein will be with us for a long time. The patient, however, invites us to look ‘through the (architectural) fantasy’ at the changing atmosphere in the psychiatric centre. In the end, the Jozef Plein is a symptom of the impossible desire of the work groups to save a building that is already gone – at least in terms of decision-making and financial operation. It stemmed from a discontent with the demolition of heritage, the alienation in the hospital infrastructure, the longing for an in-between space, and so on. By contrast, the new Lente building, renamed Dageraad, proudly takes up its new position within the psychiatric centre of the future. The management decided to have the building rearranged by its own technical department without major architectural gestures, but with an interior design that fully reflects the building’s historic character and respects the needs of patients in psychosis care – mixing the usual hospital furniture with vintage found in attics and tailor-made design. The reversal of Lente into Dageraad may therefore even be considered as more radical than the Kan. Triest Plein insofar as the old spirit of demolition is no longer of any meaning in the everyday operations of the unit for psychosis care.

After all, the new Lente building, currently known as Dageraad, is the legacy of the Jozef Plein. From the outset, the idea was to use the makeover of the Sint-Jozef building as a test site in the search for a different care architecture. The production process, from project definition to tendering, design, appropriation and post-production, enabled the Caritas Psychiatric Centre to find another way of doing care architecture. And so it happened that the management found a vision, language and tools to self-manage architecture in the makeover of the Lente building. Only a grumbler would complain about the disappearance of the architect. The ill-conceived demolition plan shows exactly what happens when architecture is left to the architect alone. And vice versa, in the words of Jan De Vylder: ‘The new Lente building is an architecture that proves the redundancy of an architect.’ After finishing the new Lente, the costs were slightly higher than expected, but still 40 per cent below the cost of a new construction. General director Herman Roose jokingly stated: ‘The costs may have risen slightly higher than we expected, but the pride of our staff is included.’

Excerpt from the essay ‘Design Your Symptom’ published in: architecten De Vylder Vinck Taillieu and BAVO (eds.), Unless Ever People, Flemish Architecture Institute, Antwerp 2018

ISBN: 9789492567079

Tags: Care, English, Psychiatry

Categories: Architecture

Type: Article