Article

What happens between the pavilion and the shooting range?

Gideon Boie and Fie Vandamme

01/06/2015, Psyche

In the socialisation of mental health care, there is a lot of focus on aligning the psychiatric centre with the outside world. However, this alignment changes little with regard to the ‘needy’ architecture that we encounter in psychiatric health care. Breaking through external boundaries is perhaps the easiest challenge. Breaking through the internal lines of separation within a psychiatric institution is a totally different issue.

Wim Cuyvers once named the provisional façade and the shooting range as the two most characteristic elements in the Flemish landscape. The provisional façade reflects the constant waiting for neighbours who never appear. The finely manicured front lawn provides the detached house with a shooting range that makes every potential intruder visible for miles. Both elements symbolise the failure to form a living community.

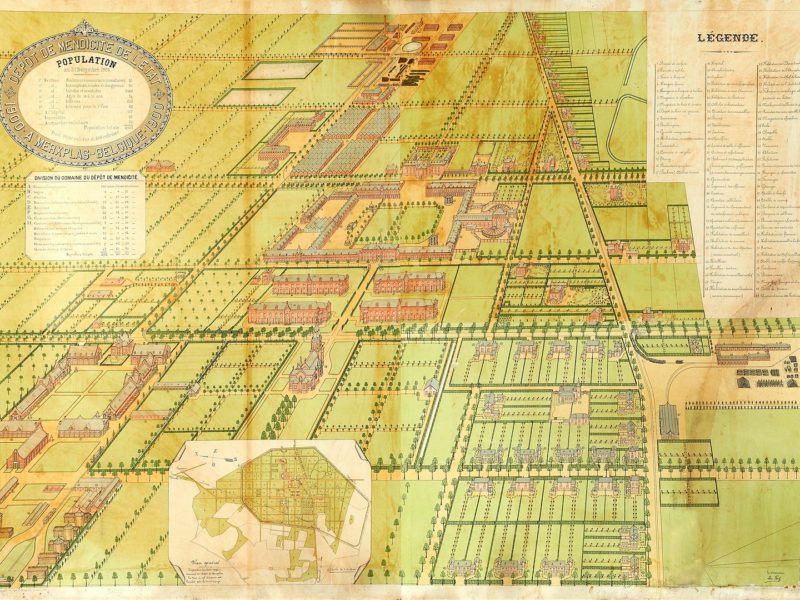

Today the establishment of a psychiatric hospital appears to be the ultimate in general spatial planning in Flanders. The two characteristic elements are the solitary pavilion surrounded by an expansive, manicured lawn. Neighbours are kept at a safe distance by the pavilions widely dispersed all over the campus. The green sea of space places all passers-by under close scrutiny, no matter where they are going or standing. A psychiatric hospital does not even aspire to form a community. Instead it aims to offer a temporary refuge to people in crisis – transience is however often an elastic concept.

We encountered this discussion at the Caritas psychiatric centre in Melle. The work groups with doctors, management, staff and patients were conducting an exploration of the psychiatric centre of the future. Doctors in particular seemed to be particularly concerned with the question of whether or not hospitals must be homely and sociable. One argument was that a patient may feel best in an unnatural therapeutic living environment. Others were of the opinion that a therapeutic setting did not necessarily imply poor architectural and spatial quality. Patients on the other hand stated that even a more humane living environment would not be able to retain them for a day longer than necessary in the psychiatric centre.

It is striking that this discussion plays out in a psychiatric centre that was established as far back as 1908 – with pavilions. In contrast to the monastic model, the pavilion model invokes the suggestion of an intimate domestic circle to which the patient retreats for rest and movement within Arcadian surroundings. In practice however, it is within the pavilions that day-to-day life is really lived. Once the patient is inside, he/she is cut off from the outside world. The sitting area is positioned with its back turned towards the outside. The bedroom has no balcony. Smokers remain close to the porch. Even rehabilitation and recreation take place in a remote room.

During the course of the twentieth century, the gardens surrounding the historical pavilions have disappeared. Buildings erected around the turn of the century stand starkly on the grass. The negation of the world outside is compensated at various places with a small courtyard and sometimes even a living space reminiscent of an agora.

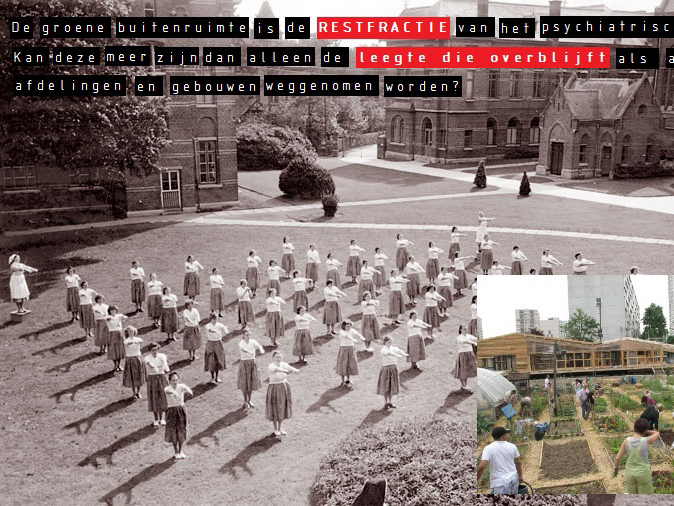

The green outside is today the residual fraction of the psychiatric centre. It is the empty space that is left behind after all the departments and buildings have been removed. It remains in oblivion except for its utilitarian functions. Sharply defined paths allow the user to move from one to the other pavilion. Shrubs and trees sporadically protect specific programmes against prying eyes. Parking is available at the front door of the pavilion.

The work groups with doctors, management, staff and patients arrived at the suggestion that space should also be created for a third room between pavilion and lawn – the intermediate space – in the psychiatric centre of the future.

In the first place, the idea of a transitional space between the inside and outside was considered. Today, there is a hard and fast dividing line between pavilion and lawn. A patio, fence, pergola, flowerbed, balcony and other garden elements that could have softened this internal border and made it more easily penetrable. The transitional space prevents a direct exposure to the public eye. This makes a discreet welcome and undisturbed stroll both possible.

The transitional space offers protection against the natural elements. A covered outdoor space encourages one to engage in outdoor activities even when it is raining or when darkness falls – even if only as a break during a stroll.

In the second place, intermediate space enjoyed a high priority from the point of view of the institution. Places in the margins of the psychiatric centre appear to offer many highly suitable options for this purpose. The forest offers options for rambling or even to run away. The enclosed outdoor area of the cemetery offers a sense of security. The bench behind Den Berg is a perfect place to meet up. The bus stop offers a good resting place. Etc..

The problem with this marginal space is that depending on illness and age, it is not always accessible to all patients at present. The challenge therefore lies in designing intermediate spaces in the heart of the psychiatric centre.

Intermediate spaces do not always require specific programming. The designation of a fixed time or place for meetings utterly destroys the spontaneity of chance encounters. The patient finds his/her rest or movement through a use of the infrastructure with the elements of serendipity, mistake or even clandestinely. This spontaneity is possible in areas that are not directly geared to provide mental health, but nevertheless offers room for the day-to-day needs and desires of patients.

English draft version of the article ‘Wat gebeurt er tussen paviljoen en schietveld?’ published in Psyche 27 (2), June 2015

Tags: Care, English, Psychiatry

Categories: Architecture

Type: Article