Article

One day at the Furka Zone

Gideon Boie

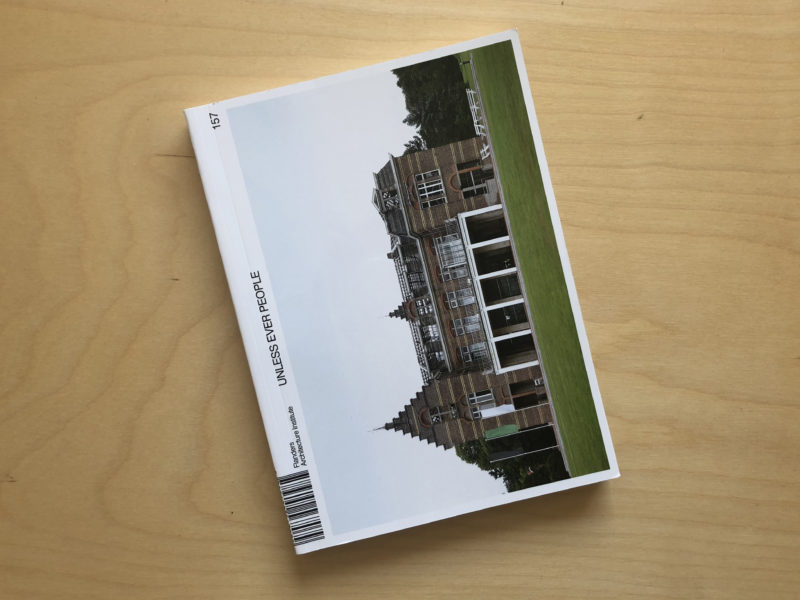

2019, Koenig Books

Image: FIlip Dujardin

The Furkart project (1984 - ca. 2000) at the high mountain pass in the Swiss Alps has become a legendary reference point in contemporary art history, inspiring works by Ulay and Marina Abramovic, Daniel Buren, Per Kirkeby, Richard Long, Panamarenko and many others. Its story has also made it into architecture history, with the much praised design by OMA for the addition of a bar and terrace to the Hotel Furkablick. A day visit to the somehow overlooked creation that is the Dépendance, designed by T.O.P. office, at the Furka mountain pass, opens up an alternative understanding of the Furkart legacy today. I will argue that Furkart speaks to the imagination not so much because of its legendary origins, but more because of its strange afterlife, subverting (confusing, if you prefer) the traditional models of art and architectural production.

1 The Tourist Trap Downstairs

When asked to write a text on the Dépandance at the Furka mountain pass in the Swiss Alps, designed by T.O.P. Office (Luc Deleu and Laurette Gillemot) in the early 1990s, in the shadow of the OMA design for bar and terrace in the Hotel Furkablick, I must admit it felt like falling from the blue sky. I vaguely remembered having read something about the OMA’s work and had no further cognitive associations that could help me to understand the urgency of the question. My petty excuse that I am not a historian, my work rather focuses on the political dimension of architecture, but this was countered by Peter Swinnen with the convincing argument “you really have to wake up once at that legendary spot.” The spectacular setting at an elevation of 2.429 m above sea level undoubtedly convinced me to embark on the journey, as well as the good company. Later, while re-reading the chapter on the bar and terrace design for the Hotel Furkablick – originally built in 1893 and extended in 1903 – in the classic OMA volume S,M,L,XL, I realise how the tourist trap is essential in the understanding the Furkart project.

The S,M,L,XL chapter title ‘Worth a detour’ plays exactly the same game.[1] The text by Rem Koolhaas is a rather bizarre staccato of text fragments in which every line holds meaning, but the overall message is a rather vague impressionistic sketch of something that seems to be quite important. The text starts with a note mentioning the Ulay and Marina Abramovic performance art installation and the Daniel Buren shutters. The note goes without any specification or explanation, assuming the reader just knows about it. Next, there is a very short historical sketch of the attempt by gallerist Marc Hostettler to turn the hotel into an art space. Incidentally, the text mentions that the mountain pass is open only four months a year, as if in a fairy tale. The narration of the hotel renovation process starts with the Koolhaas’ arrival by helicopter. The fairy tale continues. The text ends with a short description of the design, with the new entrance funnelling visitors inside the building, opening up the view to the majestic high landscape and leading them to the bathroom downstairs.

The origin myth scripted by Rem Koolhaas leaves us with the evident question: what exactly is the reason it is worth a detour? The S,M,L,XL chapter on the Hotel Furkablick is interpreted by Sabine von Fischer, in the ‘OMA, The First Decade’ issue of Oase Journal, as a sign of the ‘absence rather than presence’ of Rem Koolhaas, and linking it with the closure of Furkart around the Millennium. In fact it was more like a slow dying out process.[2] After talking with Luc Deleu and Laurette Gillemot, I understand that the writing of a text full of blank spots can also be read not just as an allusion to but as a literal consequence of Rem Koolhaas’ very loose engagement with the Furkart project. Absence dissimulated by presence. The incoherent narrative is an attempt to master the overall context, reducing the historical events to his own and diluting the involvement of other actors from the primordial scene, with everything beginning only when the architect arrives on stage by helicopter. The architect may have been absent and the overall narrative missing, but in the end, the name ‘OMA’ is the master signifier that sutures the field of floating meanings and directs all attention to itself.

The use of architecture as a machinery that first funnels the visitor and then opens up the view in the next sequence, is key to understanding the design. In the aforementioned Oase Journal, Sabine von Fischer put it like this: “The architectural intervention [OMA’s design for a bar and terrace at Hotel Furkablick] is not meant to be looked at, but to be looked out from.” Continuing with: “It is a spectacle of views, less so of functions.” Also: “It is a modernist machine for viewing, where the surroundings provide the setting and the scenery, but neither the intellectual and material context.”[3] All this may be true, but still the question remains: what about the weird climax of leading the visitor to the bathroom downstairs? It is perhaps the reason why the ‘modernist viewing machine’ was presented by Sabine von Fischer as part of an ironic strategy by Rem Koolhaas, for the wrong reason. The point is that ironic dis-identification has always been a very strong ideological tool of the exact opposite, in this case the ironic finale in the bathroom reveals that the architectural design is instrumental to the creation of an art industry in the Swiss Alps. In short, there is no Furka experience outside the OMA design, even when you are trapped in the bathroom.

2 Detour from the Detour

The reason for our trip to Furka is not the OMA extension to the Hotel Furkablick, but the Dépendance designed by T.O.P. Office. The Dépendance is a small building positioned right on the border between the Valais and Uri cantons, only 650 meters up the road from the hotel. It used to act as temporary housing for the staff at the Furka Hotel (built around 1850, demolished in 1982) on the other side of the road, and as an automobile repair shop. In 1983, Gallerist Marc Hostettler bought both the Hotel Furkablick and the Dépendance from the Müller family, who for generations has been running hotels at more accessible locations in the Furka valley. It is striking that the design by T.O.P. Office for the Dépendance is something that has gone unnoticed in most writings on Furkart, not even earning a footnote in the reflections on the OMA work at the Hotel Furkablick. Given the one-sided focus on OMA, the article by Marc Dubois in S/AM (1992) can only be read as an attempt to script an inclusive architecture history of Furkart.[4] The article presents the design for the Dépendance by T.O.P. Office next to the OMA design for the Furkablick hotel, suggesting it understands the two buildings as Siamese twins.

Actually the S/AM had published an intermediate design for the Dépendance by T.O.P. office. The first design was for the addition of an autonomous, self-supporting façade to the existing building. As the walls are not set straight, the extra façade would open up a crack, where gas tanks and electricity generators could be stored. The design was rejected by Marc Hostettler, who considered the self-supporting façade too high an expense. Now, visiting the Dépendance more than twenty years later, Luc Deleu smiles cynically: “Marc Hostettler preferred to connect the Dépendance with an electricity cable from the Hotel Furkablick and he has been digging in the rocks a whole summer long.” Luc Deleu confesses that Marc Hostettler had no real vision on architecture and directed him to Panamarenko and Rem Koolhaas. Luc Deleu smiles: “I thought: well, what does Panamarenko have to say about architecture?” Rem Koolhaas criticized the design for the Dépendance, arguing that the fourth dimension was missing. When I ask what exactly the fourth dimension refers to, Luc Deleu reacts: “Nothing, it is saying something just to say something. Anyhow, the design finally got replaced by something more poetic, purely formal, in concrete as it is more plastic than a wooden construction.”

The concrete extension at the left façade with cut-out windows is the most visible intervention at the Dépendance, respecting the existing structure as much as possible. An outdoor metal staircase is added to the façade, creating a second circulation system and making the attic directly accessible. The covering of the staircase was never realised. On the opposite façade, a concrete brick slope is added, gradually leading up to the back of the building and actually functioning as the start of the hiking route. A small concrete roof is added to a technical side room. Art works are added on the façades, such as the ‘Windline over the Furka Pass’ (1989) by Richard Long and also the ‘Empreintes de pinceau no. 50 répétées à intervalles réguliers (30cm)’ (1990) by Niele Toroni. Standing in front of the building, Luc Deleu shrugs his shoulders: “Well, it still looks the same.” Continuing to express his admiration for the modest construction: “A building that has patina does not change anymore. I mean, you don’t see the changes anymore.” Turning to Peter Swinnen: “The addition of the slab and slope is still a good idea.”

In an attempt to reconstruct the record of architectural interventions in the Furkart timeline, while sitting at the dinner table, architecture history appears to be just as confused as the family and love relations in a Greek myth.[5] First it is claimed that the date, 1991 as mentioned in the S,M,L,XL chapter on Furkablick Hotel, was an adjustment to present the OMA project as being born first. The second claim is the alleged disinterest of Rem Koolhaas, with the helicopter flight organised by Marc Hostettler as a desperate attempt to have Koolhaas on the job. The latter was “somehow forced to get on the helicopter”, says Luc Deleu, and still he wanted to leave as soon as possible as the hotel size perhaps did not fit with the grand project OMA was looking for in that period of “Bigness”.[6]

Peter Swinnen suggests an alternative history based on three different subject positions of Luc Deleu within the Furkart project.[7] The most evident contribution is the design for the Dépendance by Luc Deleu, the architect. Prior to it, Luc Deleu was involved in talks with Marc Hostettler about his (rather exacerbated) ambition to organise a CIAM-like symposium at the Furka Pass. The names of John Hejduk, Peter Eisenman, Mario Botta, Rem Koolhaas, and others were suggested by Luc Deleu, the mediator. However, originally Marc Hostettler was only dealing with Luc Deleu, the artist. The gallery owner had commissioned Deleu’s triumphal arches built with typical freight containers around 1983 on the lake of Neuchâtel. It was the same year that James Lee Byars, supposedly inspired by the car chase in the James Bond movie, Goldfinger, proposed to Marc Hostettler to do the ‘A drop of Black Perfume’ (1983) performance at Furka Pass and thus provided the earliest conception of what would be named later Furkart.[8]

3 Enter the Afterlife

Apart from its spectacular views, the addition of the bar and terrace to the Hotel Furkablick, designed by OMA, certainly has a few practical advantages for tourists: you can have a good expresso while doing field work in the mountains, and, perhaps most importantly, use the bathroom. In contrast, the Dépendance, designed by T.O.P. office, stands idle down the road. It is a mute object, a dot on the horizon negative to people cruising along in their fancy car –the perfect ‘modernist viewing machine’ if ever there was one.[9] It is clear that the building has nothing to offer, not even a public bathroom. This leads people to use the back of the building for a discrete toilet break. The informal use of the Dépendance as toilet stop for tourists urges us to shift attention from conception to consumption of the small building.

It remains unclear whether the Dépendance has actually been used for the intended use of artist residency. According to Luc Deleu, only two artists have ever made it to sleep here, as the weather conditions are too extreme at the mountain pass and the interior services are kept to the bare minimum. Panamarenko was one of them. “He was a tough one and knew how to survive in these harsh conditions,” says Deleu. For years, Panamarenko used the space as a summer retreat and workplace. This meant that the function of the Dépendance was re-conceptualised as a “total object”, a word play with the idea of a ‘total work of art’, a Gesamtkunstwerk, “where rooms are used to hang residues of art work or for artists to exhibit something.”[10] Panamarenko actually bought the Dépendance in 2004, after the Furkart project wound down around the Millennium.

Of particular interest is the actual use of the Dépendance today. As Panamarenko is ageing and suffers health issues, the building is once more abandoned. The door is opened by Janis Osolin – we will discuss his role later. In the garage we find pieces of plastic shutters used in wintertime, which starts around September and continues until May, i.e. the full period when the pass is under snow. Improvised curtains hang on the inside, seemingly as sunscreen and/or to avoid passers-by gazing in. There is a curved wall, creating a sort of counter. Luc Deleu describes it as a strategy inspired by Le Corbusier to “suggest something that is not there”. In the atelier, which appears rather empty, we find a tool box in a wheelbarrow full of brand new, almost unused equipment, such as drilling machines, paint mixers and the like. Luc Deleu grasps a bright new docking saw and says: “this is Panamarenko, when starting a new work he always bought new equipment.”

Under the attic we find Panamarenko’s living rooms, again looking as if life has suddenly been sucked from them. The hand of the architect is not particularly visible in the interior. Luc Deleu says: “The idea was that we need at least one big open space in the building.” Its subdivision into eight sleeping rooms has been taken away. Particularly striking is the informal arrangement of furniture, equipment, food, paraphernalia and rummage set by Panamarenko. The utter chaos is strictly organised in several corners of the room, radiating a divine peace of which only the artist knew the internal logic. The bread is covered with aluminium folio. The Coca-Cola bottles stand in lines. Books are put on show while standing on the floor. North arrows are drawn on the floor and walls. Laurette Gillemot confirms: “Panamarenko knew full well that everything he did or said was captured by the eagerly observant art scene.”

Our company explores the household with the guilty feeling of an intruder who knows that Panamarenko could enter at any moment, with his typical provocative idiocy. Suddenly Luc Deleu and Laurette Gillemot gaze at a white table serving as a worktable, full of scratches, notes, stains, and dirt. When Jan De Vylder and Inge Vinck enter the room, they gaze at exactly the same table. It appears to be an original white table by Ann Demeulemeester, a gift to Panamarenko when receiving the prestigious culture prize from the Flemish Community in 1998. We speculate how the naked use of art, reducing all vanity, will soon become the ultimate surplus value, making the white table part of the artist’s life story is perhaps the perfect fictive investment the art market thrives upon. It reminds us of what happened with the atelier of Panamarenko at the Biekorf in Antwerp, donated to the contemporary fine arts museum MuHKA and now curated as a holy shrine, with the public standing in long lines to pay a visit in small groups. Luc Deleu quotes Panamarenko: “when the [conservation] work is done, you can close the door and throw away the key” – knowing full well that even this act of self-subtraction will increase attention.

4 The Man Who Puts in Value

While the closed shutters of the Dépendance make clear that nothing happens on the inside, all sorts of interventions refer to the fact that the building is still in good condition. Apart from the two gigantic steel tubes in the back of the building, installed as if they have come tumbling down the mountain, discouraging toilet breaks, the clean atmosphere is striking, with the grass cut neatly around the slope, rendering the sharp corners of the concrete brick slope visible. Some of the shutters have been renovated or replaced by new ones. Colour tests are performed on the black arrow art work by Richard Long, it is a prospective work without any precise reason, carried out just in case it is ever needed. Here enters Janis Osolin again, director of the publishing house Edition Voldemeer and in charge of the Furkablick Institute, who happens to take care of the whole mountain pass area, including the Dépendance. It seems that the afterlife situation of the Dépandance is, after all, a pars pro toto for the current stage in the Furkart history.

Janis Osolin was asked by art collector Alfred Richterich to watch over the legacy of Furkart. After supporting the Furkart project for years, Alfred Richterich bought all the remains in 2004, more specifically the Furkablick Hotel, its contents and its environs. The Furkablick Institute was born. The challenge is not to re-start Furkart, but to protect its heritage and memory. This includes the conservation of the art collection, the classification of the immense archive, the organisation of the library, the compilation of a manual, the management of the Furkablick bar, and more. Strangely enough the practice lacks any institutional character, except for its name. There is no (business) plan, no defined goal, no target groups, no numbers to reach, no PR, the art works are not even mentioned in tourist brochures.

The mise-en-valeur is a new function that Janis Osolin has invented for himself in the conservation of the Furkart heritage. The Furkablick Institute distributes an orientation map with timelines that continue after 2004, adding new dates to the mise en valeur of many works. It refers to the restoration and reinstallation of art works produced in the past decade, somewhere in an empty hotel room, in the surrounding fields or in the buildings.[11] This means that, for example, the shutter works ‘Sans Titre’ by Daniel Buren appears on the timeline twice: first when produced in 1987-1989, and secondly as mise-en-valeur from 2013 to the present day. The mise-en-valeur is a strange variation to Boris Groys’ conception of the curator as the master-artist, in this case creating added value in the re-installation of the artwork.[12] Over years of commitment to “analysing history and reflecting upon any decision taken”, wrote Benoit Antille, “he managed to impose his rules and style with regard to caretaking the [Furkart] heritage.”[13]

Evidently care is much needed to keep intact the art interventions on site. Janis Osolin leads me to the Max Bill fireplace (1994), located in exactly the spot where the old Furka Hotel (demolition 1977) used to stand, and functioning today as a rest place for cyclists. He explains to me that cutting the flowers is important to accentuate the abstract form of the black granite stone blocks. Nearby stands the work ‘Furkapasshöhe’ (1986) by Per Kirkeby, a head-height hollow column in brick, at the highest point of the pass, overlooking the valley. Again, the grass here is neatly cut, and now and then inscriptions are brushed away. The issue is not so much the landscaping, but the question of the extent to which nature may take over these artworks. Janis Osolin maintains that taking care in this way makes the tourists pay more respect to the works, often voluntarily taking their rubbish with them.

The caretaking extends to the spatial setting at the Furka pass. Suddenly it becomes clear that wherever I look, stones have been placed deliberately to stop cars from driving all over, the grass is cut to accentuate a certain line in the field, the gravel is laid to finish the road infrastructure. Janis’ idea is that the introduction of ‘desire lines’ in the landscape unconsciously directs the movement of visitors to the Furka Pass. While we stand there looking at stones set in a straight line, with the grass cut neatly, something resembling an old mountain path, a couple of campers fold their tent to continue on with their journey. Strangely enough the tent was set in line facing the imaginary mountain path. In talking about the ‘Furka Zone’, Janis Osolin takes his engagement beyond the sphere of art, protecting the site by setting an atmosphere. Even the double demarcation sign between the Uri and Valais canton, the old elegant one strangely doubled with a new ‘postmodern’ version, is squared by side stones and given a platform using gravel.

5 The Zero Point of Art

In 2018 the Furkablick Institute is hosting two artists-in-residence from Colombia. One of them is Christina Consuegra, an anthropologist researching the relationship between the landscape and cheese culture. We meet in the underground kitchen of the Furkablick Hotel, where the dysfunctional kitchen robot of OMA is turned into a support for cooking plates. Christina Consuegra opens a trap door to the storage cellar. In its centre stands a cupboard filled with artisanal cheeses, each made using different ingredients and demanding specific treatments. I stand perplexed, not only by how a Colombian can acquire such a deep knowledge of the different fermenting processes of Swiss cheese, but also upon seeing the cellar turned into a Wunderkammer devoted to cheese, mimicking the other hotel rooms packed full of wonderful art objects, vintage furniture and household goods.

Leaving the kitchen, we look at ‘Le début du paysage – Col de la Furka’ (1986) by Paul-Armand Gette, a glass door with ‘0 m’ inscription. It reminds me of Friedrich Nietzsche’s words that the Swiss people have no history because there is no way for the farmer to have a look at the other side of the mountain ridge[14]. Today, in the artist residency, Nietzsche’s story is inverted. The storage cellar clearly functions as a retreat, where the artist somehow escapes the heavy weight of the Furkart history and produces meaningful new work. Artist Liliana Sánchez has also found a work space in the old lodging for hotel staff, where rooms are packed with mattresses and bed pans, using the empty floor of the living room to make one of her huge drawings reflecting the natural landscape of Furka.

Liliana Sánchez takes me on a tour. We pass through the military camps, which Janis Osolin described earlier as Gesamtkunstwerk, imagining the middle building away in order to recreate the training ground. In line with the military barracks stands building ‘N° 10’, a wooden barn that contrasts the rhythm of the military camp. N° 10 is covered with an exceptional roof, a quality one would expect to find in an old chalet or mountain chapel. Inside the barn, every three hours an installation of sixteen speakers and microphones play the ‘Requiem Aeternam’ (2009), a work by Stefan Sulzer, sung by the monks of the Einsiedeln monastery. The installation perhaps best symbolises how the Furka Zone seems to cultivate confidentiality, leaving the daily stream of tourists to pass by while the monks start their song over and over again behind the closed door.

In the garage of the former lodging for the Hotel Furkablick staff, hangs the artwork ‘Ohne Titel’ (1988) by Rémy Zaugg. Again the door is closed at all times. Liliana Sánchez carries an impressive keychain. The work is a huge white square, oil on canvas, produced in an open air mountain field, now anchored on the wall of an empty garage, hanging on a system that looks as if it has to survive eternity. The white paint is full of craquelure creating an image that could easily be mistaken for an intentional depiction of the mountain landscape. Its mise-en-valeur is listed in the time line of the Furkablick Institute orientation map and dated 2012.

A stone’s throw away stands another small barn in the field, used for the installation of two artworks within. On the door hangs a tiny metal plate with the inscription ‘Alfred Richterich Stitung / Institut Furkablick’. Liliana Sánchez searches the enormous keychain, but this time she does not find the right key. She interprets the closed door as a critical metaphor: “You have to dig into the Furka Zone. […] Furkart is a private privilege, a history accessible only to initiates.” Paradoxically the Furka Zone is open for everyone while at the same time being a closed, symbolic universe that needs not only the right door key, but the right guide to point one in the right direction, providing reading tips, contextual introduction, and so forth.

Continuing our walk, we pass the Furka Pass Cemetery (2007), a square form in a curve along the road. It looks like the foundations for something that was never built, but could equally be an unused crib, filled with beautiful flowers and weeds. Hidden in the green lies the ‘Gedenkbarren fur Leigh Markopoulos’ (2017), a commemoration put by Kate Fowle and Janis Osolin. In an attempt to see the grazing Valais Blacknose close up, we climb. Taking a rest on an high elevated rock formation, overlooking the Hotel Furkablick, the military camp and the road winding up to the Dépendance, the valley opening onto the horizon, Liliana Sánchez confronts me with the fundamental question of the Furkart legacy today: “What is the minimum level needed to keep going, the minimum level to make sense, the minimum to sustain itself, the minimum to relate with the public?”

6 Epilogue

Many texts on Furkart are written as an abstract out-of-time reflection, perhaps knee-deep in the hagiographic tradition. One cannot write about the OMA Hotel Furkablick design as if we are still in the 1990s. Including the T.O.P. Office design for the Dépendance in architecture history without opening up the scope to the changing framework of Furkart into the Furkablick Institute would fall into the same trap. Gallerist Marc Hostettler has left the stage and with him the idea of attracting the public with art and architecture produced by big stars and using the Furka landscape as a majestic backdrop. Today, the maintenance of the artworks has itself become a work of art. The great artworks are kept in immaculate condition, living an (almost) invisible existence, an immortalized body allowing the tourists to enjoy the exceptional mountain site.

The role of Janis Osolin as the one who ‘puts in value’, backed by the investment of spiritus rector Alfred Richterich, certainly shows great respect to the Furkart legacy but, equally, it marks a rupture with the past. My question ‘mise-en-valeur for whom?’ was answered poetically by Janis Osolin: “Momentary visits is the possibility of the Furka Zone and that is the element we protect.” It is difficult today to understand why one would invest financial and human resources simply to generate momentary visits”. In any case, the so-called Furka Zone opens up a “rare opportunity to think in total opposition to the art market’s obsession with visibility, accessibility, and return on investment.”[15] For the moment I conclude that the Furka Zone is but a private collection of great art and architecture that happens to be located on a high mountain pass in the Swiss Alps, accessible only four months a year.

While taking a rest in the Furkablick bar, Luc Deleu finds a postcard with an image of Panamarenko’s ‘Green Rucksack Flight Test’ (1987) performance. When I describe the performance as a pose, Luc Deleu reacts furiously “No, it is not a fantasy, it is real.” He tells an anecdote. Apparently Panamarenko wanted to use a real motor block in the performance and showed a catalogue to Marc Hostettler, indicating a very specific type. Marc Hostettler considered the price far too high and offered to buy a second hand model. As Panamarenko refused stubbornly, Marc Hostettler gave in and bought a brand new motor block. When the motor block arrived at Furka, Panamarenko was as proud as a child, but said: ‘it [the motor block] is too heavy’, so he took a metal saw and cut away the cooling fins, arguing ‘these are not really functional.’ While I think of how to construct an argument that defines the whole Furka Zone as the architectural counterpart to the green rucksack flight test, an extremely serious fantasy space, a heterotopia, Luc Deleu continues his story undisturbed: “Panamarenko wanted to build the green rucksack in Furka only, because he believed that if the rucksack could fly in Furka, it would be able to fly anywhere.”

Notes

[1] Rem Koolhaas, Worth a detour, published in: Rem Koolhaas, S,M,L,XL, Monacelli Press New York 1995, pp. 127-129.

[2] Sabine von Fischer, Intervention versus Narrative, published in: Christophe Van Gerrewey and Véronique Patteeuw (eds.) Oase Journal #94, NAi010 Rotterdam, 2015, pp. 97-103.

[3] Ibidem.

[4] Marc Dubois, Furkablick: OMA en Luc Deleu, published in: S/AM #92/2-3, Stichting Architectuurmuseum, Gent, pp. 12-21.

[5] Peter Swinnen, A Swiss Übung, included in this book.

[6] Rem Koolhaas, Bigness or the Problem of the Large (1994), published in: Rem Koolhaas, SMLXL, Monacelli Press New York 1995, pp. 515.

[7] Peter Swinnen, A Swiss Übung, included in this book.

[8] Ziggurat special on Furkart, produced by Annie Declerck and directed by Karel Schoetens for the Belgian television network TV1, broadcasted in 1994.

[9] Paul Virillio, L’Horizon Negative, Editions Galilée, Paris 1984.

[10] Ziggurat special on Furkart, produced by Annie Declerck and directed by Karel Schoetens for the Belgian television network TV1, broadcasted in 1994.

[11] Furka Zone orientation map, published by: Institut Furkablick, Alfred Richterich Stiftung, Edition Voldemeer Zürich, June 2018.

[12] Boris Groys, Art Power, MIT Press, Cambridge (Massachusetts) 2008.

[13] Benoit Antille, The Removal of Context: a methodological statement? Published in: Creative Villages? #3, École Cantonale d’art du Valais, February 2017, pp. 3-7.

[14] Read the preface in: Friedrich Nietzsche, Untimely Meditations, Second Part: On the use and disadvantage of history for life, originally published in 1874.

[15] Ibidem

Bibliographic note: Gideon Boie, “One Day at the Furka Zone”, in Peter Swinnen, ed., Luc Deleu: Dépandance Furkapasshöhe. Set 1 / Zine 2 (London: Koenig Books, London, 2019, 5-64). Part of the ‘Carrousel Confessions Confusion’ book series edited by Jan De Vylder at ETH Zürich.

—

Tags: English

Categories: Architecture

Type: Article