No wonder the second lockdown causes a claustrophobic emotion among people. We break out of the oppression of the private house en masse. Walking, jogging and cycling is the favorite recreation during the pandemic. A day back at the office feels like a true liberation, even if we get stuck in traffic on our way. A visit to the museum is a relief, even if it is only allowed for just one hour. Not to mention the clandestine lockdown parties, despite the police warning to use drones for control.

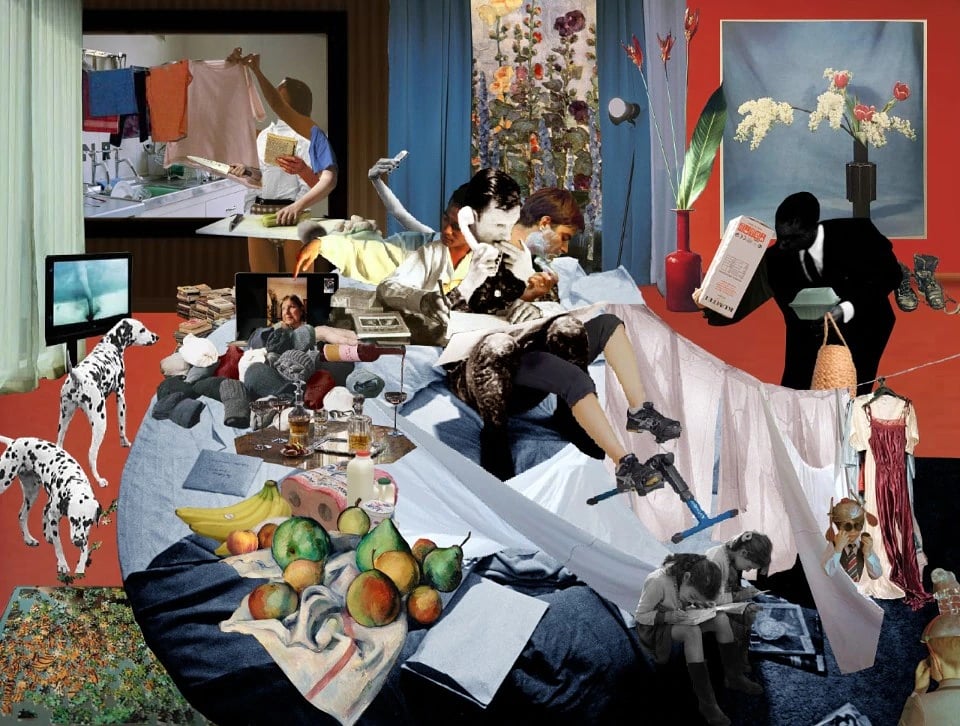

Working from home became the norm during the pandemic, but that was long overdue. Talking about the omnipresence of the (hospital) bed in the pandemic, architectural historian Beatriz Colomina referred to the iconic images of Hugh Hefner, who worked from his round bed at the Playboy Mansion in Los Angeles. The bed was a veritable control room from which the ‘contemporary recluse’ – that is how Hefner called himself – arranged all sorts of things. Not in a tailor-made suit, but in a dressing gown with slippers.

Today everyone became a playboy, although the atmosphere of decadence has long vanished. In the fight against the Coronavirus, telework became an ethical duty. Working from bed – the elementary part of the private home – came in handy for the sake of public health. Shabby clothing is no longer an obstacle. Teleworking from home makes it possible to keep the economy running during lockdown, guarantee education, enjoy culture, meet friends and much more.

However the playboy’s phantasy doesn’t seem to be that exciting at all, it is more of an agony. The (un)voluntary recluse is part of a capitalist system that colonizes every minute for production and consumption, wrote Beatriz Colomina long before anybody heard of Covid-19. In her vision the internet was especially designed to make the private sphere part of productive life. Working from home frees us from commuting, but not from stress, depression and violence.

That is not the only problem. In the background of the iconic black and white photo by Magnum photographer Burt Glinn we see a housekeeper serving Hefner. The man in the background – not coincidentally a person of color – does sit tight in his suit to do the job. The parallel with our Corona time is obvious, now that homeworkers can call on suppliers, who ring the doorbell every five minutes with packages and prepared meals.

Not that the Corona-playboy is having an easy time. On the contrary, the agenda of the Corona-home-worker, too, is filled to the brim. Combining life and work is one thing, but in the lockdown the household duties are added, not to forget home schooling and babysitting. Schools are closed not so much because they are the major breeding ground for the Corona virus, but to shut down social traffic. Leaving all the care tasks to the woman in the house is no longer an option.

The question is how to solve the housing issue in times of Corona. It is doubtful whether expansion of the home is a solution, because the pressure on the private sphere manifests itself just as much in the suburban villa. An interesting proposal came from Flemish Government Architect Erik Wieërs, who saw Corona as an extra motivation for collective living: while the housing units are kept private, the Corona safe bubbles are surrounded by a zone of common facilities preventing us from total alienation.

At the same time, the challenge is to make space for the contemporary household staff. In fixing our existence, keeping it safe from Covid, we can no longer be as selfish as Hefner. A good start lies in the organisation of distribution points per district, to minimize the movements of parcel services in our streets. Setting up local production centres would be even better, but needs a more radical change in urban economy. After all, the walk to the distribution point is a good alibi for the teleworker to go out again.